21 Elephants Walked Across the Brooklyn Bridge in 1884 to Prove Its Safety

When the Brooklyn Bridge opened on May 24, 1883, it immediately captured the city’s attention. Stretching between Manhattan and Brooklyn, it was the longest suspension bridge ever built, and people were eager to see it up close. The very next day, more than 150,000 pedestrians crossed it, along with around 1,800 vehicles. The bridge held steady, and New Yorkers began using it almost without hesitation.

Still, there was unease beneath the excitement. Suspension bridges had a troubled past, and earlier collapses had not been forgotten. One failure in West Virginia in 1854, triggered by strong winds, lingered in public memory. For many residents, the sheer size of the Brooklyn Bridge made it feel uncertain, and that quiet worry followed the crowds during its first week.

Panic Changed Everything Overnight

Everything changed on May 30, 1883. Memorial Day brought huge crowds to the bridge, with estimates putting the number of pedestrians close to 20,000. Near a narrow staircase at the Manhattan entrance, someone stumbled. Screaming followed, and two opposing streams of foot traffic jammed together. Confusion spread fast. People fell, and others kept pushing, unsure of what was happening or why.

By the end of the chaos, 12 people had died, and dozens more were seriously injured. Later investigations confirmed that the bridge itself never failed. It stood solid throughout the panic. Still, public trust took a hit. The structure survived, but its image suffered. Even so, people kept using it. Trains running across the bridge carried about nine million passengers in the first year, and that number doubled the next year. The bridge had become essential, even as lingering fear refused to fully disappear.

Enter P.T. Barnum With a Very Public Idea

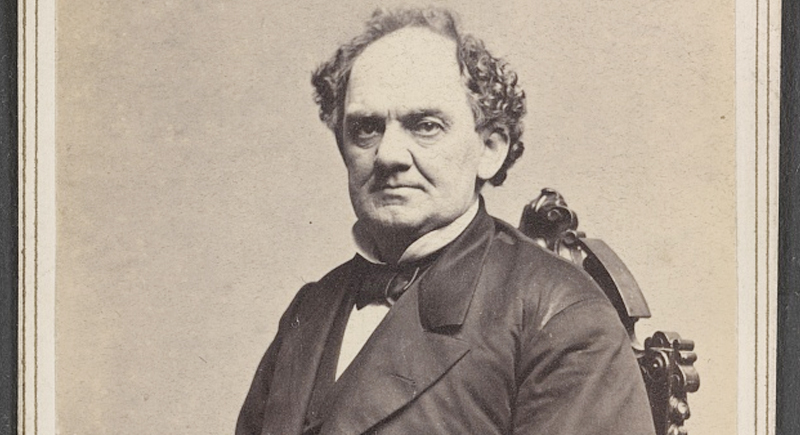

Image via Wikimedia Commons/Charles D. Fredricks & Co.

Bridge officials faced a challenge. Reassurance through math or engineering diagrams would not calm a shaken public. A visible demonstration seemed like the only option. P.T. Barnum was a showman who had already floated an idea earlier. He offered to march his circus animals across the bridge for a $5K fee.

The proposal went nowhere, but after the stampede, the tone shifted. This time, the parade came with no toll attached. Barnum understood crowds. He also understood symbolism. If enormous animals could cross the bridge without issue, the message would land fast. The plan gained approval.

The Night Elephants Took Over the Span

Image via Getty Images/Tomasz Dutkiewicz

On the night of May 17, 1884, the Brooklyn Bridge became an unlikely stage. Just days before the anniversary of the deadly stampede, P. T. Barnum set out to make a statement. He led 21 elephants and 17 camels onto the bridge, turning a place of recent fear into a slow, deliberate parade. Bringing up the rear was Jumbo, his massive six-ton African elephant, while thousands of onlookers lined the route, watching the animals make their steady way across the span.

Photography struggled in low light at the time, so images of the crossing never surfaced. Newspapers filled the gap. Coverage framed the event as spectacle and reassurance rolled into one. The bridge held. The animals crossed without incident. The crowd watched the proof arrive step by step. The effect of this caused public anxiety to ease. The bridge regained its footing in the city’s imagination. Over time, it shifted from risky experiment to daily routine.

Why Elephants Worked When Words Failed

The choice of elephants made sense because weight had meaning. An elephant represented certainty in a way figures on paper never could. The parade also blended entertainment with infrastructure, two forces that shaped public opinion during the late nineteenth century.

The Brooklyn Bridge did not need testing. It needed trust. Barnum’s procession delivered that through visibility and scale. The stunt became part of the bridge’s story, sitting alongside years of construction, innovation, and loss that preceded opening day.

The bridge still stands today as one of New York’s defining landmarks. Its early years show how fear and faith often collide when progress arrives faster than comfort. In 1884, reassurance walked across steel cables on four massive legs, and the city believed again.