Animals That Can Change Their Sex Naturally

Reproduction in the animal world does not always follow a fixed script. In several species, individuals shift their biological role from male to female, or vice versa, when social structure or environmental conditions demand it. This flexibility keeps breeding cycles moving even when partners disappear or temperatures rise. From reef fish to reptiles, these changes follow predictable biological rules that help populations survive.

Clownfish

Credit: Getty Images

Life inside a sea anemone runs on a strict hierarchy for clownfish. Every group has one breeding female, one breeding male, and several smaller juveniles. All start life as males. When the female disappears, the breeding male takes on the female role, and the largest juvenile steps up. This keeps reproduction active without adding new members.

Bearded Dragons

Credit: Getty Images

These lizards use chromosomes like mammals, yet temperature still holds power. When eggs incubate above 32 degrees Celsius (89.6 degrees Fahrenheit), individuals with male chromosomes can develop as functional females. These females lay eggs and often produce about twice as many as standard females. Rising heat has increased the frequency of this reversal in the wild.

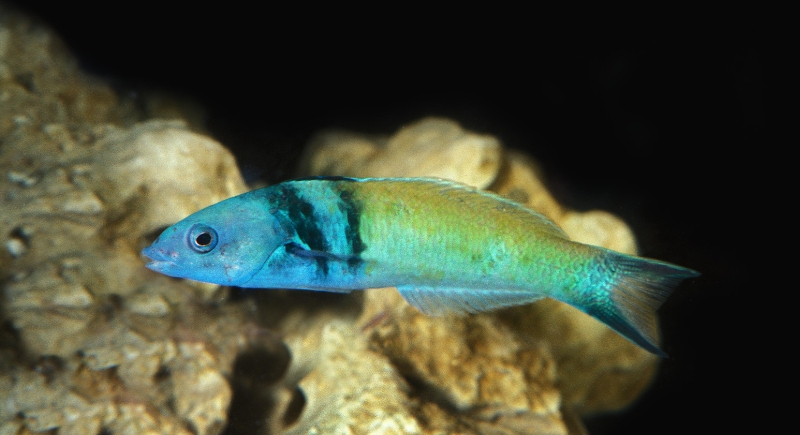

Bluehead Wrasse

Credit: Getty Images

Coral reefs rely on order, and bluehead wrasse enforce it quickly. Groups contain one dominant male and many females. If the male vanishes, the largest female changes role within about 8 to 10 days. Ovaries convert into sperm-producing tissue fast enough to avoid a breeding gap, which helps maintain stable population numbers.

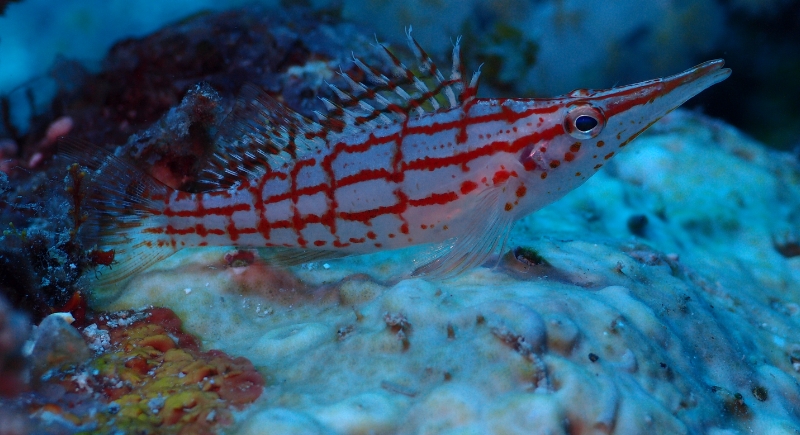

Hawkfish

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Social flexibility sets hawkfish apart. These reef fish usually begin life as females and can shift into males when harem structure demands it. What makes them unusual is reversibility. If a new harem loses too many females or faces pressure from a larger rival, a former female that became male can switch back again.

Black Sea Bass

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Along the U.S. East Coast, black sea bass manage reproduction through population awareness. Individuals begin as females and may later become males. The switch often occurs when the number of nearby males drops. This response balances breeding opportunities across wide geographic ranges where finding partners can be unpredictable.

Humphead Wrasse

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Around the age of 9, large humphead wrasse females may adopt the male role. Color changes follow the shift by moving from reddish tones to blue-green. These fish can live up to 30 years, but heavy fishing pressure has reduced their numbers despite this built-in reproductive flexibility.

Banana Slugs

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

On forest floors, banana slugs handle reproduction differently. Each individual carries both male and female organs simultaneously. Self-fertilization is possible, though rare. Most pair up and exchange sperm so both partners produce fertilized eggs. This system works well in damp habitats where encounters can be slow and infrequent.

Green Frogs

Credit: pexels

Green frogs show that flexibility is not limited to marine life. Tadpoles may develop according to genetic instructions, then reverse later under certain conditions. Field studies confirm this happens in both clean and polluted ponds. The ability helps local populations adjust their ratios when environments shift unexpectedly.

Humpy Shrimp

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

This shrimp follows a tight schedule. Individuals function as males during their first year. In the second year, they switch to the female role, lay up to 3,000 eggs, and die soon after. Their larger body size supports egg production, which explains why the change occurs late and only once.

Swamp Eels

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

All swamp eels hatch as females, but maturity brings options. Some gradually change into males over about 30 weeks. During the transition, both ovarian and testicular tissue are present. The shift can reverse if female numbers drop.