10 Animals That Live Shockingly Long Lives

We tend to think of animals as short-lived, especially when we compare their lifespans to human lifespans. But some species move through the world at a completely different pace. While generations of people come and go, these animals keep living, aging, and surviving far longer than most of us would ever expect.

Greenland Shark

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

For years, Greenland sharks baffled researchers because nothing about them hinted at extreme age. The breakthrough came when scientists dated proteins in the eye lens, which forms before birth. Results showed individuals living roughly 250 to 500 years, meaning some were already alive in the Middle Ages.

Ocean Quahog

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Ocean quahogs look like unremarkable clams at first glance, but their shells tell a detailed life story. Each ring marks a single year, which lets scientists determine their age with rare precision. Many live past 200 years. One specimen, nicknamed Ming, was later dated at 507 years old, placing it among the longest-lived non-colonial animals ever recorded.

Bowhead Whale

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Bowhead whales revealed their age by accident. Researchers recovered stone harpoon points from the 1800s embedded in living whales. Analysis of eye tissue confirmed the finding. Some individuals lived beyond 200 years, with estimates approaching 250. They were alive before modern technology reached the Arctic and still move through the same cold waters today.

Aldabra Giant Tortoise

Credit: Canva

On the Aldabra Atoll in the Indian Ocean, giant tortoises spend their days moving slowly between the same grazing patches, water sources, and shade. Many individuals reach at least 150 years, with documented cases beyond 180, with routine barely changing over decades.

Koi Carp

Credit: Getty Images

In Japan, koi are raised under carefully controlled conditions, often in ponds kept by the same families for decades. Many live past 100 years. One well-documented fish reached 225, with paper records tracking ownership and age, turning certain koi into living historical records rather than pets.

Albatross

Credit: Getty Images

Albatrosses age slowly by design. They take years to reach maturity, breed infrequently, and return to the same nesting sites again and again. One Laysan albatross, known as Wisdom, lived past 70. With few natural predators, their greatest risks now come from fishing gear that cuts short lives meant to unfold over decades at sea.

Rougheye Rockfish

Credit: Getty Images

Deep-water surveys off Alaska and British Columbia revealed rockfish that had been reproducing for far longer than expected. Ear bone analysis later confirmed ages surpassing 200 years. That slow, extended life strategy works until fishing comes into play. Removing older fish strips populations of their most productive breeders, turning longevity into a vulnerability rather than an advantage.

Tuatara

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

On predator-free islands in New Zealand, tuatara live at a pace that barely registers on a human calendar. Growth continues slowly for decades, and reproduction may happen only once every ten years. Individuals often live to 100 years, since their long lives are tied to evolutionary isolation, with replacement occurring so gradually that population loss takes generations to correct.

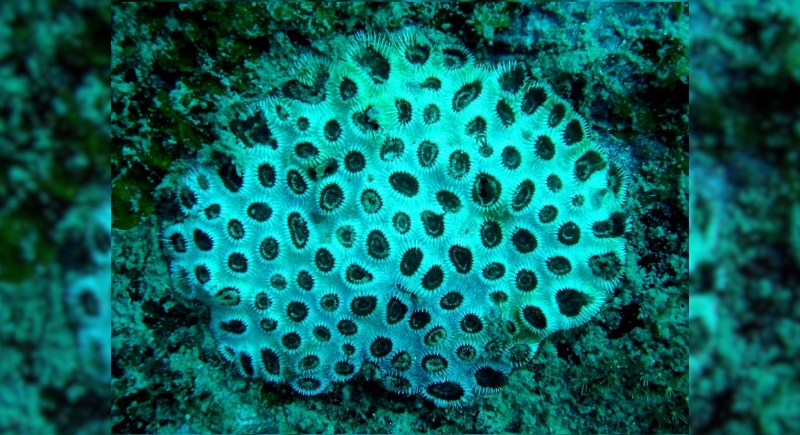

Black Coral

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Divers exploring deep reefs sometimes mistake black coral colonies for rock formations, and radiometric dating later showed why. Some colonies are more than 4,000 years old, growing only millimeters per year. Layer by layer, they record shifts in ocean chemistry and temperature, functioning less like animals and more like historical ledgers anchored to the seafloor.

Lobster

Credit: Getty Images

A lobster’s age shows up in size, scars, and the number of times the animal has survived molting. American lobsters never stop growing, and estimates suggest some can reach around 100 years old. Molting replaces damaged shells and tissues, keeping bodies functional. In practice, fishing usually ends their lives long before biology does.