Apparently, Tadpoles Lose Their Lungs Forever (And Still Stay Alive)

Some tadpoles break the rules of biology. Instead of developing lungs as they grow, they lose them entirely and still manage to survive. A recent study from Cornell University found that these amphibians adapt by finding other ways to breathe in places where most life would fail. Their DNA still holds the design for lungs, yet evolution has chosen a different route, one that keeps them alive in ways scientists are only beginning to understand.

How Tadpoles Normally Breathe

Image via Getty Images/Ken Griffiths

Tadpoles usually rely on three methods to get oxygen: gills, lungs, and their skin. Gills extract oxygen from water, while lungs and skin absorb it from air. During development, most tadpoles grow lungs before becoming frogs, which also depend on lungs as adults. Scientists once assumed that if lungs were lost through evolution, species could regain them later because the genetic instructions remained intact.

The new research challenges that assumption. Tadpoles that lost lungs millions of years ago never redeveloped them, even under conditions that made them useful again. Instead, they continued using other respiratory methods. This shows that evolutionary change doesn’t always follow logical repair.

Clever Breathing Alternatives

Without lungs, tadpoles depend on creative adaptations to bring in oxygen. The African red toad tadpole, for instance, has a thin crest of blood-rich skin on its head. It presses this crest against the water’s surface to absorb oxygen directly from the air. This structure acts like an external breathing pad and allows the tadpole to live in water with very little oxygen.

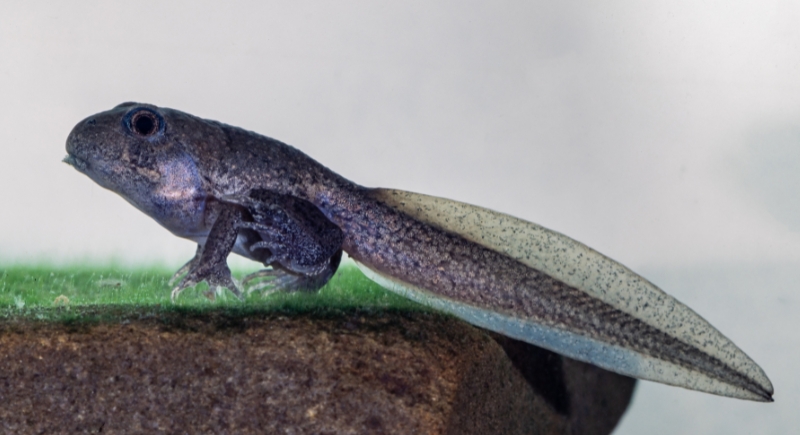

Another example is the Pacific tailed frog tadpole, which lives in cold, fast streams. It doesn’t float to breathe; instead, it clings to rocks using a sucker-shaped mouth. Both cases highlight how tadpoles replace lungs with entirely different tools for survival. These modifications aren’t simple substitutes, but fully evolved systems that perform the same essential task in new ways.

Researchers found 28 separate instances of lung loss among 530 species, which proves that this change occurred many times across unrelated frog families. Evolution seems to favor these efficient alternatives.

Stream Life and Survival Strategy

Image via Getty Images/Tolga TEZCAN

Streams create conditions that make lungs unnecessary or even risky. Fast-moving water holds abundant oxygen, so gills and skin breathing provide enough to support life. Lungs, by contrast, add buoyancy that can lift a tadpole toward the surface and carry it downstream. A body that floats easily becomes a liability in a strong current.

Many stream-dwelling tadpoles avoid that problem through physical features that keep them anchored. The northern torrent frog tadpole, found in Borneo, has a broad belly sucker that helps it grip rocks against the flow. Meanwhile, others hide beneath gravel or leaf mats to stay still.

In these environments, the absence of lungs becomes an advantage. Tadpoles that rely on gills and skin respiration stay closer to the streambed, safe from being washed away. As time passes, this advantage reinforces the lungless trait across generations. The result is a consistent pattern where losing lungs improves survival in highly oxygenated habitats.