These Animals Can Regrow Limbs, Eyes, and Even Organs

Regenerating body parts might sound like science fiction, but certain animals do it with precision and consistency. Scientists study them closely to better understand the biology behind healing.

These animals challenge assumptions about how creatures repair and rebuild body parts.

Sharks

Credit: flickr

Unlike humans, sharks never run out of teeth. A new tooth moves forward like on a conveyor belt and seamlessly replaces the old one. Some sharks replace teeth every couple of weeks, while others do it over months. The simplicity and consistency of this process make sharks important in dental advancements.

Skinks

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

When predators close in on skinks, they detach their tail, which keeps twitching and draws attention away. Within a few months, a new tail grows in, and it differs slightly in shape, structure, and even tissue composition compared to the original. But it still helps with balance and quick escapes.

Axolotls

Credit: flickr

Biologists have been fascinated by axolotls for over a century. These aquatic salamanders, native to lakes around Mexico City, can regrow spinal cords, limbs, skin, and even pieces of their brain. Their controlled restoration process could be key to treating human nerve injuries and organ damage.

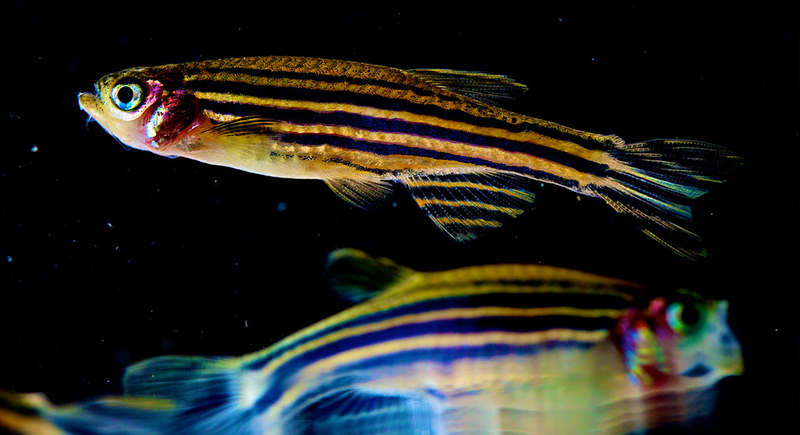

Zebrafish

Credit: flickr

First studied for regeneration in the 1990s, this small freshwater fish stunned researchers by rebuilding not just fins but complex organs like kidneys, spinal cords, heart tissue, and brain regions. Every system in their bodies follows a distinct repair process. Unlike many species that lose regenerative ability over time, this fish retains it into adulthood.

Sea Squirts

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Sharing a circulatory system allows colonial sea squirts to revive entire individuals when separated, a trait that continues to intrigue researchers. Genetic studies revealed that about 77 percent of their genes overlap with humans, which is surprisingly relevant to medical science.

Sea Stars

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Many species of sea stars contain essential organs in their arms, which helps explain why they survive major injuries. If a predator tears off an arm, the sea star often rebuilds it without issue. In some cases, a single severed arm with part of the central disk can grow into a whole new animal.

Planarians

Credit: flickr

Planarians stand out in biology labs for regenerating entire bodies after injury. These small freshwater flatworms can redevelop heads, eyes, tails, and internal organs—even when sliced into multiple pieces. Every fragment forms a complete worm. Their secret lies in neoblasts, stem cells that generate any needed tissue.

Deer

Credit: pexels

Antlers might seem like simple structures, but their growth rate is among the fastest in the animal kingdom–over a quarter inch per day during peak periods. Male deer restore and shed their antlers yearly. These bones are the only mammalian appendages that repair completely.

Salamanders

Credit: flickr

Over 700 species of salamanders work differently in regeneration. Some salamanders can fill out a limb in just a few weeks, while others take months. The pace and completeness of healing vary by species, age, and even environment. This range gives a natural comparison set to study what accelerates or hinders recovery.

Sea Cucumbers

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

As soon as they feel threatened, sea cucumbers do something extreme—they eject internal organs to confuse predators. It sounds like a desperate move, but they don’t stay damaged for long. Depending on the species, they can regenerate soft internal tissues in anywhere from a week to several months. That level of recovery, especially for delicate organs, continues to draw scientific interest.

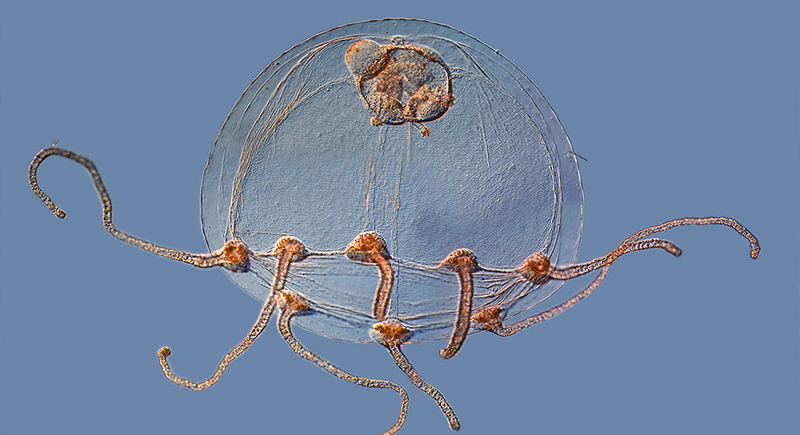

Hydractinia

Credit: flickr

Clinging to hermit crab shells, Hydractinia relies on regeneration to survive constant environmental stress. If they couldn’t restore lost heads or feeding structures, they’d likely starve or be overrun by competing organisms. Their ability to restore these parts quickly keeps their colonies functional. At the cellular level, they retain stem cells that behave much like those in embryos.

Chameleons

Credit: pexels

Most people know chameleons for their color shifts, but few notice their limited healing powers. Unlike salamanders, their ability to regrow nerves is still under study and appears far less extensive. What scientists find useful is how skin and tissue recovery involve coordination across systems. They offer subtle insights into vertebrate healing, especially how external wounds repair without major scarring.

Conchs

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Studying conchs to understand eye regeneration has become an increasing focus in marine biology. Experts are drawn to their ability to rebuild fully functional eyes in just a few weeks—a rare trait among gastropods. Plus, their eyes are perched on long stalks and prone to injuries, so this rapid recovery is essential.

Mexican Tetras

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Initially discovered in Mexican rivers and caves, the Mexican tetra evolved into two distinct populations: surface-dwelling fish and blind cave fish. This divergence created an unexpected opportunity for research. When professionals removed heart tissue, the surface fish healed by cultivating it again, while cave fish formed permanent scars.

Crayfish

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Losing a claw or neural function without the ability to regenerate would leave crayfish at a major disadvantage. Without regrowth, injuries could impair feeding, defense, or mobility, and make survival difficult in the wild. Their ability to restore both limbs and neurons ensures they remain functional after damage.