10 Facts About Octopuses That Prove They Might Be Aliens

Octopuses have a way of making familiar rules feel optional. They live on Earth but behave like visitors with a different instruction manual. Scientists study them for answers about intelligence and evolution, and writers keep circling back to them for the same reason. These facts show how octopuses bend biology in ways that feel strange yet are grounded in real research and observation.

Their Brains Are Spread Throughout Their Bodies

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

An octopus has a brain, sure—but most of its neurons live elsewhere. Roughly two-thirds of them are packed into the arms, which gives each arm its own decision-making power. This means an arm can hunt, taste, or explore without checking in with headquarters.

They Can Edit Genetic Messages on the Fly

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Octopuses possess a rare ability to edit RNA after DNA sends instructions. This allows rapid changes in how proteins are built without altering the underlying genetic code. Scientists have linked this process to survival in cold environments, where nerve function must adjust quickly. Most animals abandoned this ability long ago, yet octopuses kept it.

Their Intelligence Evolved Without Social Support

Credit: Tripadvisor

Intelligence usually grows in social animals that live long lives and learn from others. Octopuses don’t do that. They’re mostly loners who don’t raise their young and often live just a year or two. Yet they solve mazes, remember solutions, and can even open jars.

Their Bodies Can Change Shape Without Limits

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

An octopus has no bones and no rigid structure to restrict movement. Muscles provide both strength and support, which allows the body to flatten, stretch, and twist. Any opening wider than its beak becomes passable. This design allows escape, hunting, and exploration in tight spaces.

They Use Tools Without Being Taught

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Tool use is supposed to be a marker of intelligence, and octopuses pass that test with no help. Coconut shells, empty clam halves, even discarded bottles—if it can be used for shelter or defense, they’ll figure it out. What’s odd is that they don’t learn it from others. The behavior just shows up.

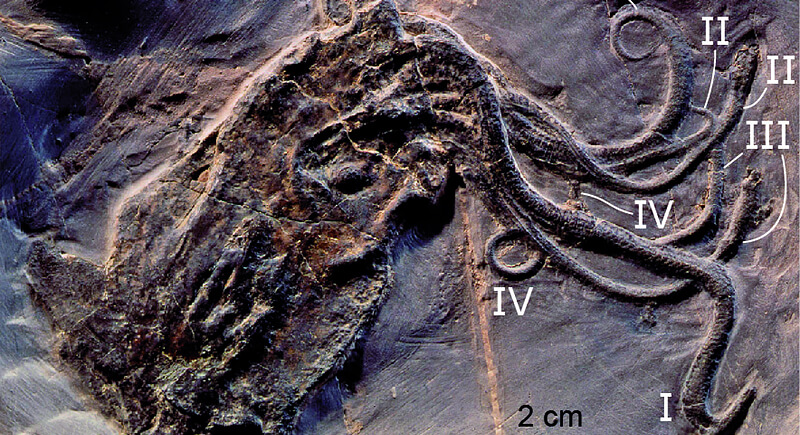

Their Fossil History Leaves Major Gaps

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Octopuses appear in the fossil record with little evidence of gradual development. Soft bodies rarely preserve well, which explains part of the mystery. Still, the jump from shelled relatives to modern octopuses feels sudden. Scientists continue to search for missing links that clarify this transition.

They Can Camouflage Without Normal Color Vision

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Octopuses change color, pattern, and texture almost instantly. Research suggests their eyes detect limited color detail compared to human vision. Their skin contains light-sensitive cells that react directly to the environment. Signals move quickly from skin to nerves, producing accurate camouflage.

Their Blood and Circulation Follow Different Rules

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Instead of iron-rich red blood like humans, octopuses use copper-based hemocyanin, which turns their blood blue. They also have three hearts: two for pumping blood through the gills and one for the rest of the body. When they swim, the main heart takes a break, which might explain why they’d rather crawl.

They Display Distinct and Lasting Personalities

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Aquarium staff often report consistent differences between individual octopuses. Some approach humans calmly. Others spray water, dismantle equipment, or avoid interaction. These behaviors remain stable over time. Personality in a short-lived invertebrate challenges assumptions about emotion and individuality. It suggests internal states that guide behavior beyond basic survival instincts.

They Feel Familiar Yet Fundamentally Unfamiliar

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

When octopuses rest, scientists have observed their skin cycling through flashes of color and texture. These patterns closely resemble the same camouflage displays used while reacting to threats. Researchers have confirmed that octopuses enter distinct sleep-like states, including a quieter phase and a more active phase marked by movement and skin changes.