The Story of How Ham the Astrochimp Went to Space

Before any human dared orbit the stars, a young chimpanzee named Ham took the leap. His journey from the jungles of Cameroon to a NASA launchpad involved confusion, bananas, and a brush with celebrity. Here’s how a curious little primate ended up making history on a rocket bound for the unknown.

Captured Far From Home

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Ham’s story began in the forests of French Cameroon in the late 1950s. As a baby, trappers captured him and shipped him to the Miami Rare Bird Farm in Florida. The U.S. Air Force later bought him for $457 to help test whether complex tasks could be performed in space.

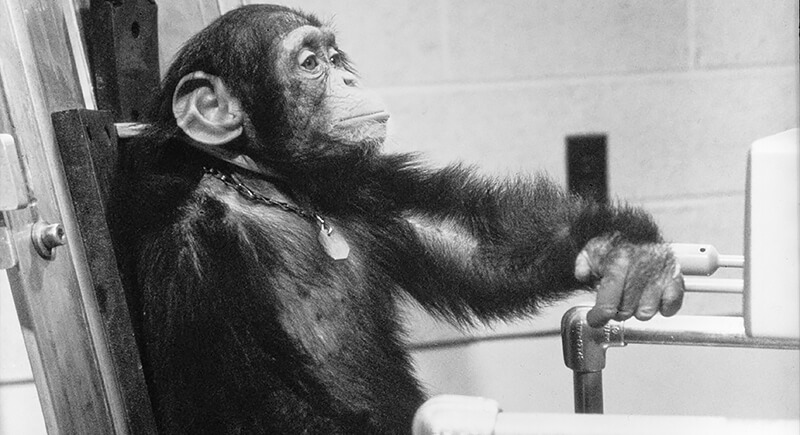

Known Only As Number 65

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Scientists kept his identity anonymous to avoid public backlash if something went wrong. They called him Number 65 throughout training. Even among handlers, he was more commonly referred to as “Chop Chop Chang” than by any formal name. NASA didn’t want headlines mourning a named chimpanzee.

Trained With Treats And Shocks

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

He trained with 39 other chimps at Holloman Air Force Base for 18 months. The goal was to hit the right lever within five seconds after a colored light flashed. The task was simple but crucial for testing brain function in space.

He Handled Stress Like A Pro

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Number 65 stood out for staying calm under pressure. During training in simulated G-force and weightless environments, his performance barely faltered. Scientists needed a subject who wouldn’t panic. His cool response in high-stress drills made him the top pick for America’s first chimpanzee space mission.

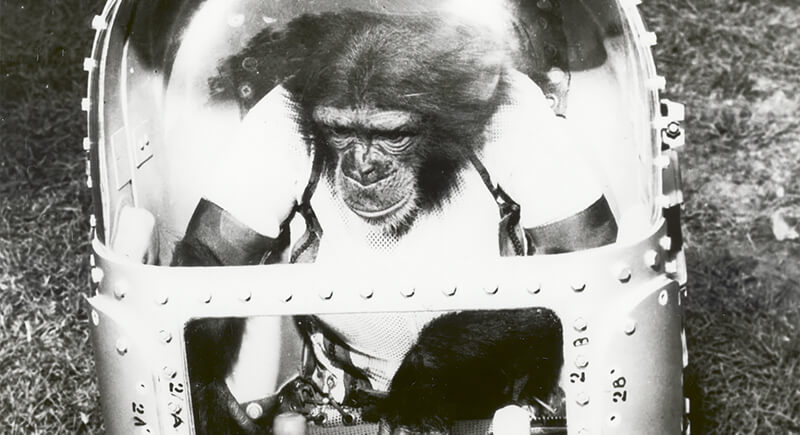

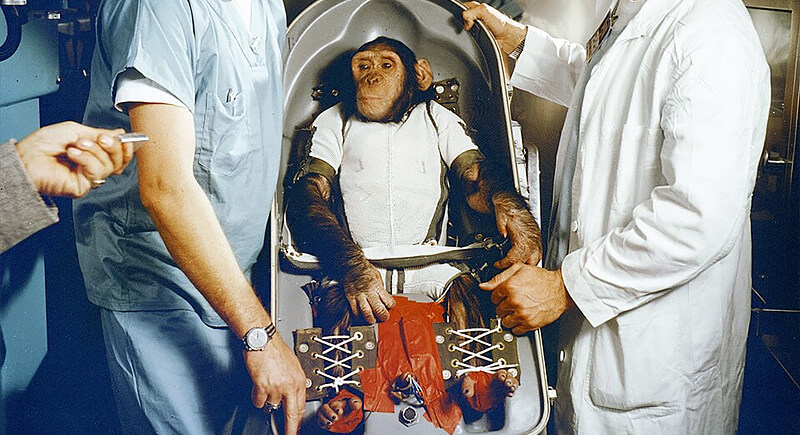

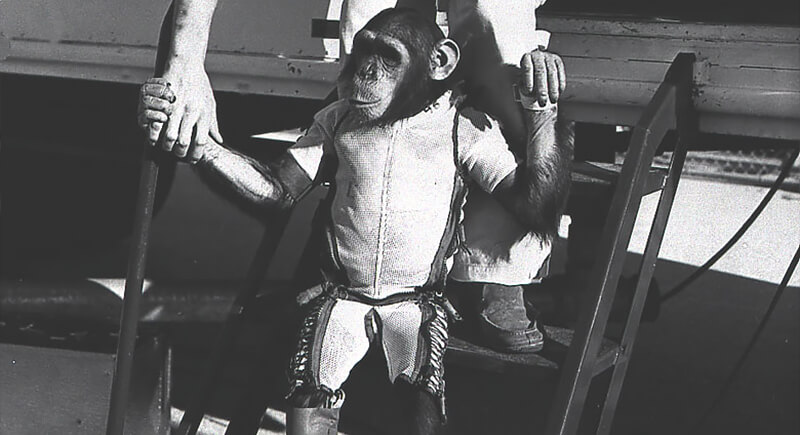

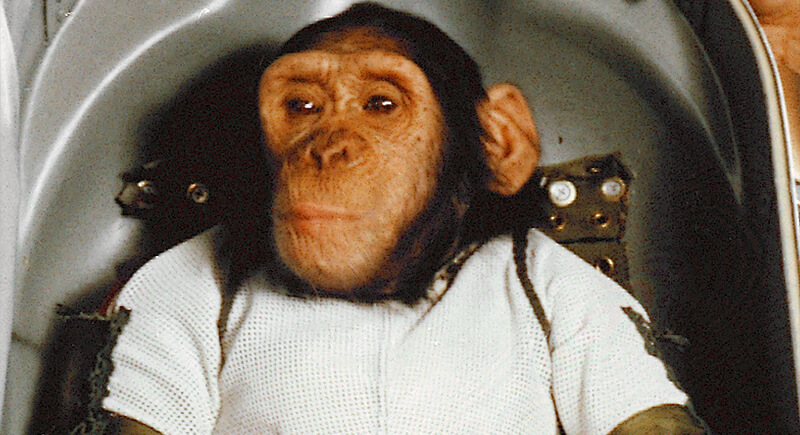

Strapped Into A Couch

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

On January 31, 1961, Number 65 was loaded into a “biopack couch,” a container fitted to monitor his vitals and control his movements. Wires and restraints kept him in place, while sensors tracked everything from heartbeat to reaction time. The countdown began at Cape Canaveral.

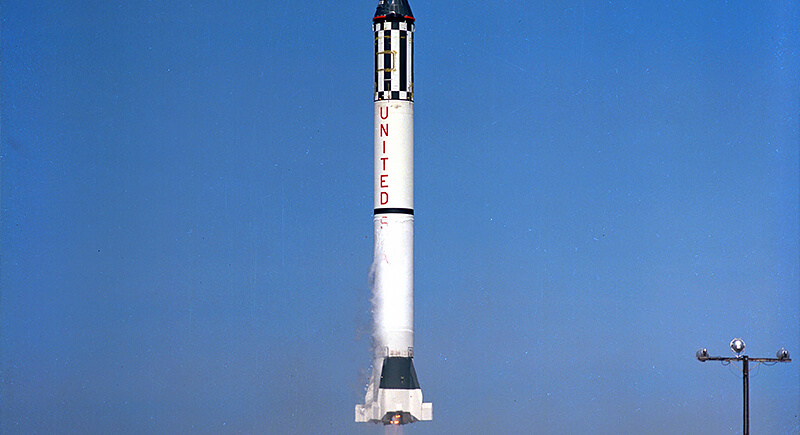

A Rocket That Overshot Its Mark

Credit: Wikipedia

The Mercury-Redstone 2 flight didn’t go exactly as planned. A malfunctioning valve delivered extra thrust, sending the capsule higher and faster than expected. Instead of 115 miles, it soared to 157. The spacecraft lost its retro-rocket pack along the way, which meant Ham had a bumpier ride than engineers had hoped.

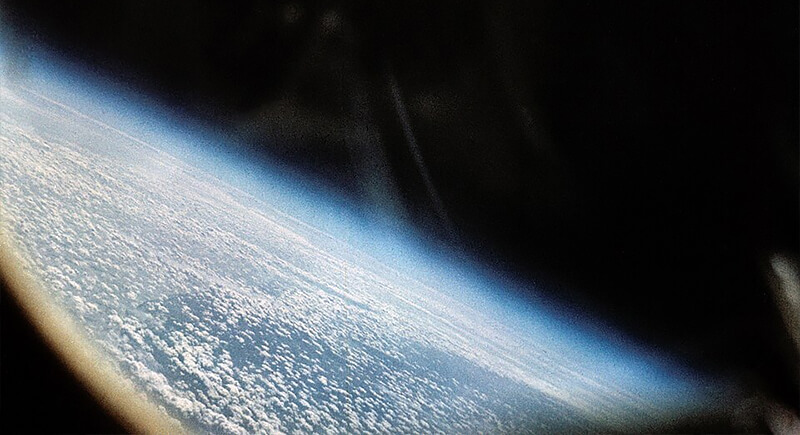

His Reflexes Still Worked In Space

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Weightless and strapped in, Ham still managed to perform his tasks midflight. He hit the levers almost as quickly as he had on Earth. The entire flight lasted 16.5 minutes, with 6.6 of those spent in microgravity. That small success gave NASA the confidence that humans could work in space.

The Splashdown Wasn’t Smooth

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

The capsule landed 420 miles off target in the Atlantic Ocean. Water started seeping into the damaged heat shield. For nearly three hours, the chimp drifted alone in the floating capsule until the USS Donner recovered it. Had they taken longer, Ham could have drowned.

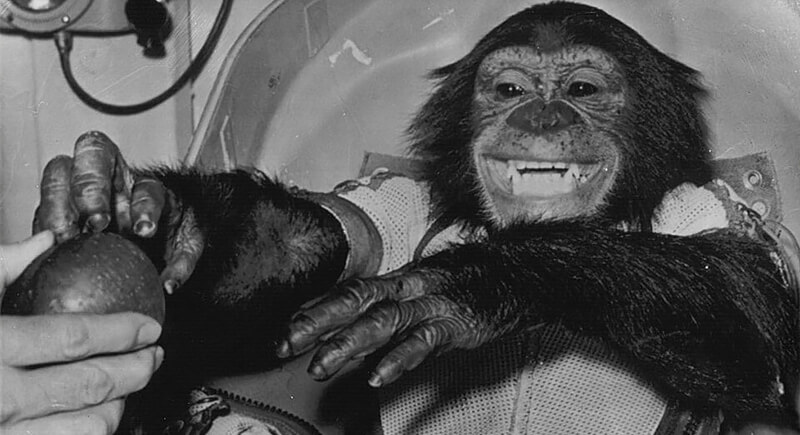

A Grin That Meant Fear

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

When rescuers pulled him from the capsule, photos showed him grinning widely. Many took it as a smile, but primatologist Jane Goodall later clarified that the expression showed terror, not joy. The camera flash and crowd noise only added to his distress.

Refused To Get Back In

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Publicity photos were needed, but Ham wasn’t having it. When handlers tried placing him back into the capsule for one last shot, he fought back. Several grown men couldn’t convince the small chimp to re-enter. His defiance said more than any press release could.

He Got A Name After The Flight

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

After the mission’s success, Number 65 finally got a name: Ham. The name was an acronym for Holloman Aerospace Medical Center, the facility where he trained. That simple rebranding helped the public see him as more than an anonymous test subject.

Lived Solo In D.C. Zoo

Credit: Instagram

In 1963, Ham was moved to the National Zoo in Washington, D.C. Unfortunately, he lived alone for 17 years. Zoo visitors often agitated him, and media attention made it worse. Solitary confinement in a public enclosure wasn’t much of a reward for surviving space.

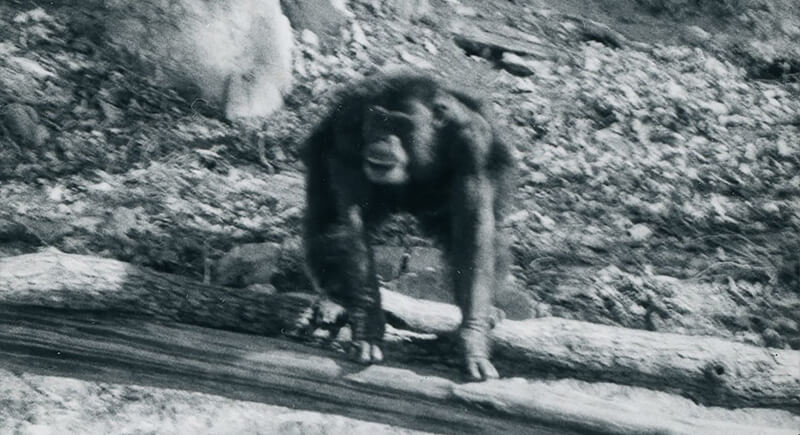

Moved To Better Conditions Later

Credit: Instagram

Public concern eventually led to his transfer to the North Carolina Zoo in 1980. There, Ham lived with other chimps for the first time since infancy. Years of isolation made social reintegration difficult, but at least his final years were spent with his own kind.

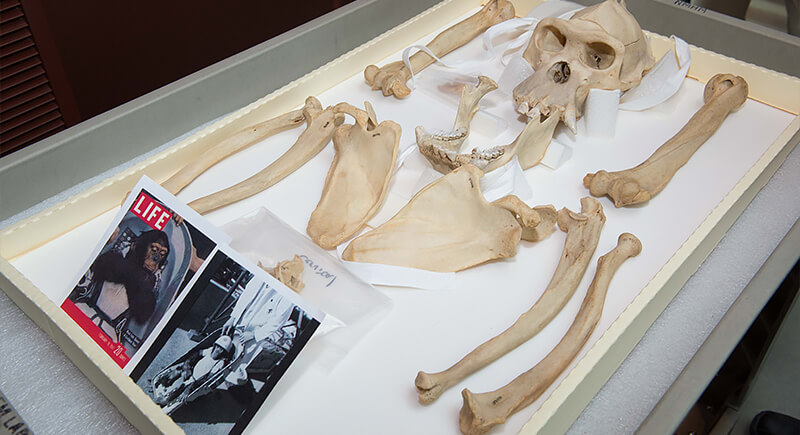

Smithsonian Had Grim Plans

Credit: X

When Ham died in 1983, the Smithsonian wanted to put his body on display, but the idea hit a nerve with the public. People pushed back hard, and plans for taxidermy were scrapped. Instead, part of Ham was laid to rest in New Mexico, and his skeleton ended up at the National Museum of Health and Medicine.

Left A Complicated Legacy

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Ham’s mission paved the way for Alan Shepard’s spaceflight, but his life also stirred debates about animal ethics in science. He didn’t choose this journey, but his performance changed what NASA believed possible. Today, Ham is remembered not just for what he did, but for what it cost him.