How an Army of Flightless Birds Defeated the Australian Military in 1932

In 1932, an unlikely conflict unfolded in Western Australia that left military leaders puzzled and historians amazed. Over 20,000 emus—large, fast-running, flightless birds—descended on farmlands already struggling with drought and economic hardship. The government responded by sending armed soldiers with firearms to solve the problem.

But despite firepower and planning, the flock proved nearly impossible to stop. The operation ended with damaged crops, wasted ammunition, and a permanent mark in military history.

Veterans Faced Drought and Debt

After World War I, many Australian veterans received land in Western Australia as part of a resettlement program. These plots sat on marginal ground, often far from towns or reliable infrastructure. Officials hoped the land would give former soldiers a fresh start. But by the early 1930s, the situation had deteriorated. The global depression crushed wheat prices. Subsidies promised by the federal government never came. Farmers expanded crops to stay afloat, which made the sudden arrival of massive emu flocks even more damaging.

These animals ended up trampling crops and smashing fences, leaving open paths for rabbits and other pests. Farmers had no extra resources to handle the invasion. Requests for help went unanswered until they proposed a solution familiar to anyone with military experience: machine guns. Their logic was simple: the weapons worked in war, so why not use them again?

The Authorities Sent Guns, Not Solutions

The Australian Minister for Defence, George Pearce, approved a plan to send military support. He viewed it as a low-cost training exercise. The federal leadership supplied soldiers and equipment, while farmers covered food, housing, and other logistics. Major G.P.W. Meredith led the operation. With him were Sergeant S. McMurray and Gunner J. O’Halloran, along with two Lewis machine guns and 10,000 rounds of ammunition.

The assignment was straightforward: reduce the emu population, which is threatening wheat production in the Campion district. Rain delayed the mission’s start until November. When it began, the challenges became obvious. The invaders moved too fast and rarely stayed in groups long enough for an ambush. Early attempts to shoot from a fixed position failed. The troops then tried mounting a gun on a truck and hoped to chase and fire at the same time. That plan failed, too. The trucks couldn’t keep up on rough terrain, and the gunners couldn’t aim during movement.

The Birds Proved Shockingly Difficult to Kill

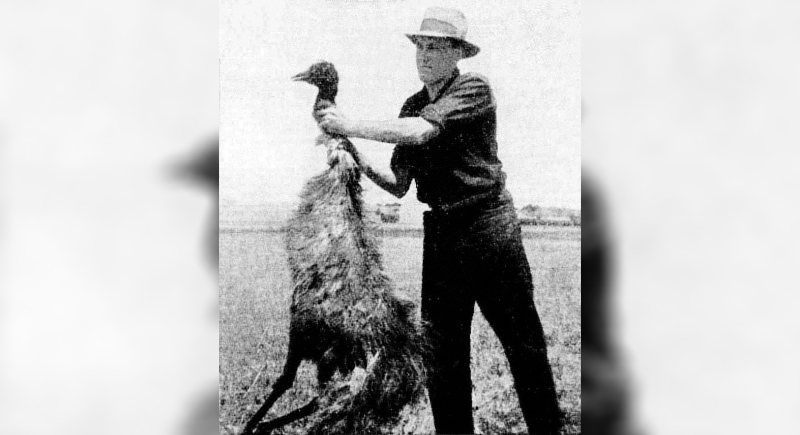

Image via Wikimedia Commons/The Land Newspaper

Military reports described the emus as unexpectedly resilient and well-adapted to avoid attack. Their size alone made them hard to bring down quickly. Some creatures kept running even after being shot and disappeared into the bush. Their tough hides made glancing shots ineffective.

By the end of the first week, only a few hundred birds had been killed. Over 2,500 rounds had been used. One observer noted that some flocks appeared to have lookout birds, which stood alert and warned others before the troops got close. Gun jams and poor visibility added to the difficulty.

At one point, an emu crashed into a truck and caused it to veer off and hit a tree. That incident summed up the entire effort: disorderly and ineffective. Even with all the firepower available, the army could not stop the emus from moving across farms and continuing to damage fields. The authorities eventually ended the operation after public embarrassment and media ridicule.