15 Lost Species Scientists Are Trying to Bring Back

It’s no longer just a fantasy in science fiction. Some extinct animals really are coming back. Using genetic engineering and preserved DNA, scientists are trying to resurrect species that disappeared decades, centuries, or even thousands of years ago.

As amazing as it sounds, these projects raise important questions about conservation, ecosystems, and what “wildlife” could mean in the future.

Dodo

Credit: flickr

A team managed to reconstruct the dodo’s genome with the help of museum specimens. Success would mean Nicobar pigeons laying the eggs and giving the dodo another shot at existence. But first, scientists must introduce enough variation into the DNA to avoid a population of clones.

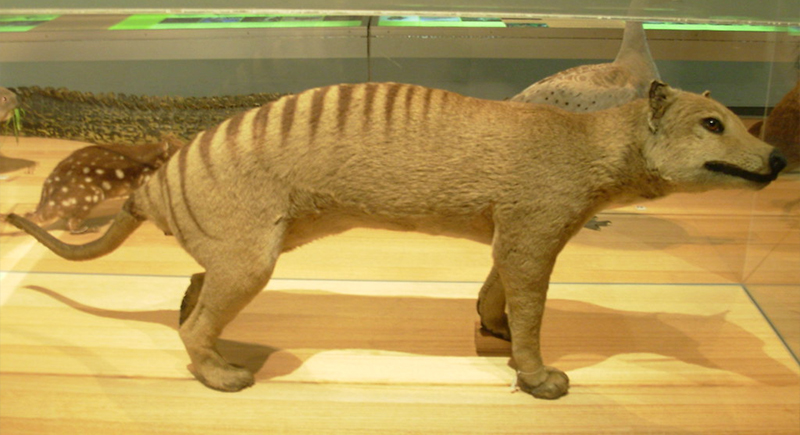

Tasmanian Tiger

Credit: flickr

Also known as the thylacine, this striped marsupial carnivore disappeared in the 1930s. Back then, people believed it was a threat to livestock and hunted it to extinction. But its DNA lived on, and scientists have already managed to insert some of its genes into mice.

Pyrenean Ibex

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

In one experiment, researchers created a cloned ibex embryo that survived to birth, but only for seven minutes. The cause of death was lung failure. Still, the birth marked a milestone, as this was the first time a vanished species was cloned and born, no matter how briefly.

Passenger Pigeon

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

At some point, passenger pigeons filled North America’s skies in flocks so large they stretched for miles. By 1914, they were gone, wiped out by hunting and habitat loss. Currently, band-tailed pigeons are being engineered to develop characteristics resembling their extinct predecessors. If all goes well, the first chicks could hatch soon.

Aurochs

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Aurochs were towering, horned beasts that predated modern cattle by centuries. Instead of using cloning, experts are selectively breeding existing cattle that still carry ancient traits. The Taurus Project in the Netherlands has spent years crossing southern European breeds to recreate the aurochs’ body size, shape, and grazing habits.

Saber-Toothed Cat

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

It’s hard to think of a more iconic Ice Age predator. Those teeth are unforgettable. But turning the saber-toothed cat into a living animal again is a long shot. While fossil evidence has survived, usable DNA is scarce. At this stage, the concept is largely speculative and faces major scientific hurdles.

Woolly Mammoth

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Researchers produced mice with dense, golden fur to test how mammoth genes are expressed in living animals. They’re also using elephant stem cells to develop embryos that could support mammoth traits. Once mammoth-like embryos are ready, Asian elephants will be used as surrogates.

Moa

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Moa’s DNA has been reconstructed based on preserved material in old eggshells. However, the problem arises when we realize no close living bird is big enough to carry its embryo. Artificial incubation has been floated as an option, though the tech isn’t ready yet.

Ground Sloth

Credit: flickr

These Ice Age giants were closely related to the modern three-toed sloth, but the size difference makes cloning difficult. Artificial wombs are also not yet equipped for it. And until those tools exist, the ground sloth will stay in the realm of theory.

Carolina Parakeet

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Once native to the southeastern U.S., the Carolina parakeet was wiped out by the early 20th century. Its bright feathers were fashionable, and that made it a target. Teams are working on building a viable genetic match, aiming to grow it inside a compatible bird species.

Woolly Rhinoceros

Credit: flickr

These tundra giants once roamed with mammoths, and their remains have turned up in frozen ground across Eurasia. Researchers are questioning whether any wild habitat still exists that could support these giants and be adapted to the cold like they once were.

Irish Elk

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

The Irish elk was one of the largest deer species ever, with massive antlers spanning more than 12 feet. Reviving them one day will be feasible, but space is the problem. Some debate where these animals belong—labs, zoos, or nowhere outside of theory. Even if the science works, release plans are far less certain.